Gas production and no pipeline? A solution worth considering

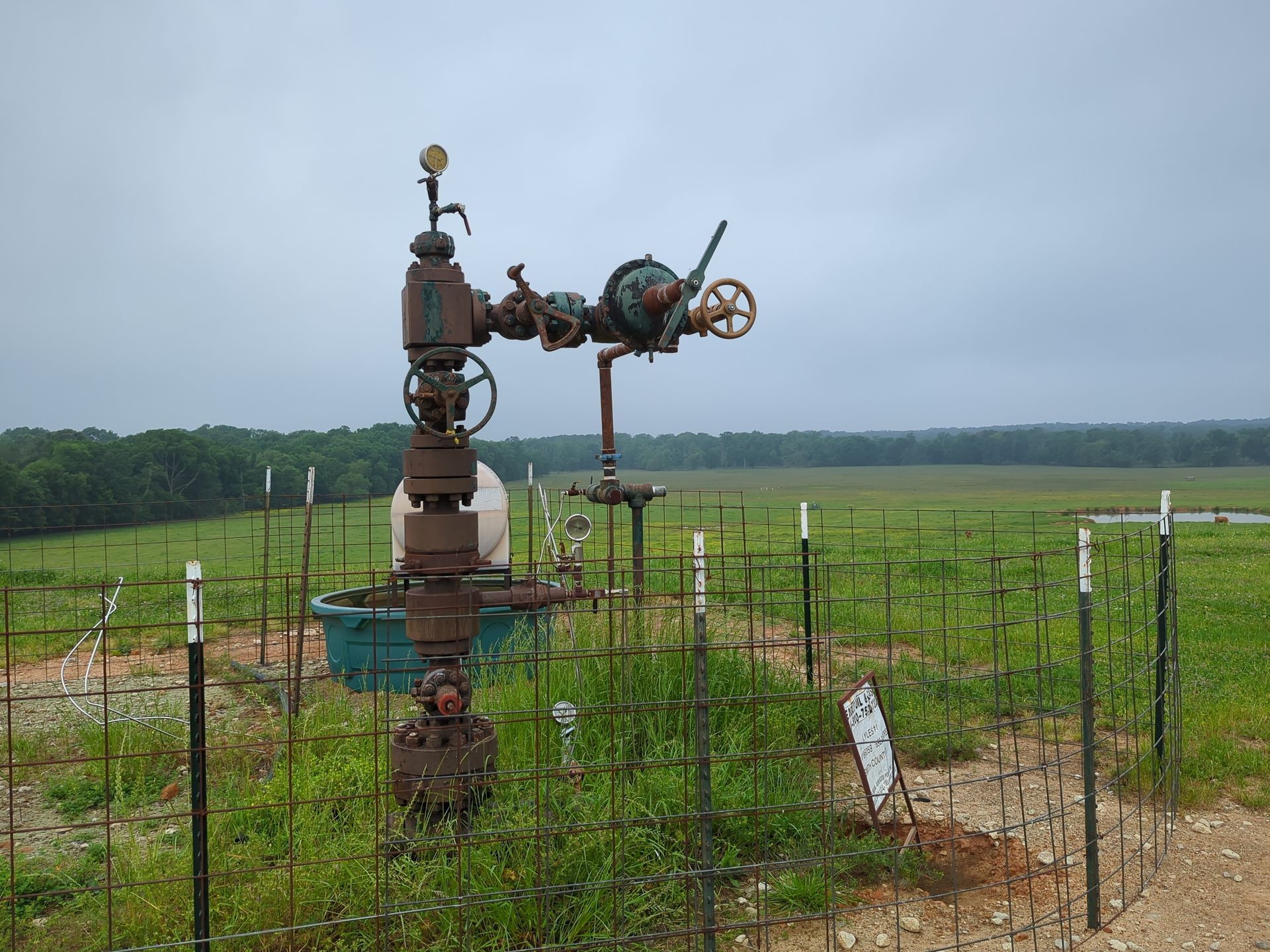

In a rural area of south central Texas, a small, one-man operating company manages a handful of oil wells. These oil wells have been around for a few decades, with peak production in the mid-1990's. For the small operator, keeping these wells running isn't a bad deal - after paying for upkeep, maintenance, electricity, and water disposal, he nets anywhere from $1,000 to $3,000 a month. He enjoys the monthly income, but he's bothered by one simple fact about these wells - leaking gas emissions. There is enough gas coming out of the wellbores to be a health concern. The gas is also highly flammable. These wells are also within a few hundred feet of houses, and he doesn't like affecting the air quality in their backyards. All of this makes the operator uncomfortable, but what other choice does he have? If he is going to produce oil, there will be gas emissions. He can't simply put a valve on the wellhead to block gas emissions because it will build up pressure until it becomes a hazard of its own. The real question is: Why is there no way to capture and sell the gas by tying into a gas pipeline?

You see, in the early days of the oil boom, in some cases the primary focus of production was oil, which, when produced, could be easily stored in tanks and transported in barrels and on railways. Gas production was initially more difficult to capture and transport. Underground pipelines needed to be installed to connect the field to the nearby urban area. The earliest pipelines date back to the late 19th-century, and the first major long-distance pipeline was the "Wabash Pipeline", constructed in 1906 to transport natural gas from fields in Indiana to the city of Chicago, Illinois. But not all oil and gas fields were developed with pipelines for natural gas production. Many fields produced predominantly oil, and the economics never worked out to build a pipeline to produce and transport the little natural gas production. For this field in south central Texas, no pipeline was ever installed for gas production and transportation.

In the fields with no gas pipeline, historically what happened with the associated gas? In most cases, it was flared (or burned) off. Flaring was viewed as an easy and inexpensive way to mitigate risk and destroy waste products. In the US, flaring continued as an unregulated activity for nearly the first century of the oil and gas industry. It wasn't until the mid-20th century that environmental concerns arose regarding the negative impact of flaring.

Regulations restricting the quantity of flaring began in the US in the 1960's. Over time the regulations restricting venting and flaring became more and more stringent. Most recently, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) released its final rule in December 2023, which established the most aggressive regulation to date. In addition to reporting and leak detection requirements, operators are now also subject to a methane tax on facilities that are out of compliance with emissions guidelines.

These regulations have dramatically reduced gas emissions as an industry. Most of the large oil and gas companies have improved their field operations dramatically over the last 50 years of increased regulation. In many cases, however, the small and very small well operators haven't improved field operations in decades. Many do not have the capital to improve operations in such a way to be compliant with these regulations. Others simply don't know the regulations or don't know how to improve field operations. Additionally, most of these small operators slide under the radar of the state regulatory agencies. For example, as long as the small operators are doing the minimum to keep the agency satisfied, the agency won't harp on them to reduce the quantity of gas they vent to the atmosphere. Because of this scenario, our small operator in south central Texas will continue to emit his associated gas production with no consequences.

Other than vent the gas, what options does the operator have? Without a pipeline to sell the gas to, options are very limited. In theory, operators can hook the gas up to a generator on site to produce electricity. That electricity could be tied into the local power grid or used for other on-site or nearby electrical demands. But is that a realistic scenario for most wells? Not at all.

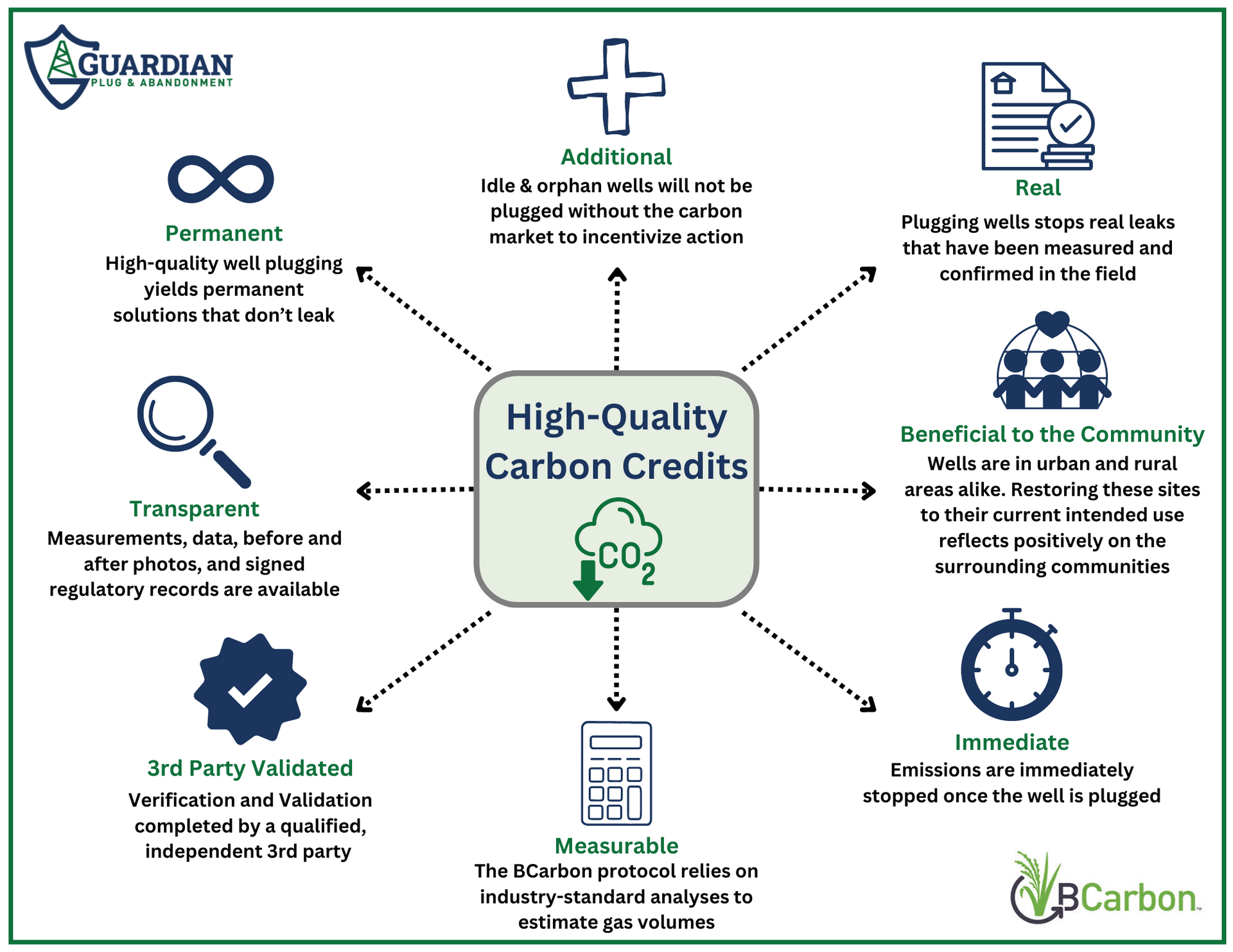

A more universally-realistic and obvious alternative to venting the gas is to permanently plug and abandon the wells. On the surface, however, this sounds like an extremely uneconomical option due to the reduction in monthly revenue and an expensive bill for well plugging and land restoration. Fortunately, companies such as CarbonPath and BCarbon are helping incentivize small operators to close their marginal, leaking oil and gas wells. By plugging these wells and permanently stopping future greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere, carbon offset credits can be generated following the calculations established in their methodologies. Here is how it works:

1 - Identify wells with remaining oil and/or gas production and gas leaks at the surface.

2 - Calculate the total reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by plugging the well.

3 - After the well is plugged, generate carbon offset credits, with each credit equaling 1 metric ton of CO2e.

4 - Sell these carbon credits to companies that have pledged "net zero emissions" to offset their carbon footprint.

Perhaps our small operator could generate tens of thousands of carbon offset credits from plugging his gas-leaking oil wells in south central Texas. Not only would he be taking positive climate action, but he also has the possibility of recovering his plugging cost and beyond by selling these carbon credits.

Guardian Plug & Abandonment is a project developer that can help small operators such as our friend in south central Texas. We will determine the carbon credit value of your well and conduct the field work necessary for the carbon project. Reach out with questions at info@plugandabandonment.com or visit our website at https://www.plugandabandonment.com/.